Nepal's iconic Juju Dhau--King Curd--adapts with time, but tradition at risk

Jul 01, 2025

Bhaktapur [Nepal], July 2 : Inside a modest factory nestled in the heart of Nepal's Bhaktapur, Rina Suwal moves swiftly between steaming vats of milk and rows of pitchers waiting to be filled.

From early morning until late evening, she is immersed in a daily ritual that has become her life's work for the past 25 years -- preparing Juju Dhau, the famed "King Curd" of Nepal.

This delicacy holds a cherished place in the Newa community, particularly during festive seasons, where no celebration feels complete without it. But as time has passed, the very vessel that defines Juju Dhau -- the traditional mud pitcher -- is slowly being replaced, threatening to erode a piece of cultural identity.

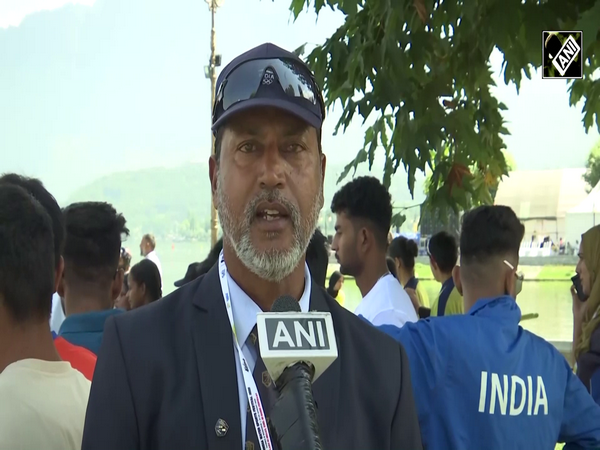

"When I started working (making Juju Dhau), only the mud pitcher was used; there was no such existence as plastic containers. About five years after I started the business, plastic containers came into use, giving comfort and easing mobility. People found it troublesome to carry the pitcher on a motorcycle from one place to another, where plastic containers became handier. In those days, people were reluctant to buy the Juju Dhau made in a mud pitcher rather than a plastic container, but now the tables have turned upside down," Suwal told ANI.

For centuries, Juju Dhau has been inseparable from the kataaro, a clay pot that not only holds the curd but also helps create its signature texture and flavour. Even as it lines supermarket shelves across Kathmandu Valley today, its roots trace back to 13th-century Bhaktapur, where tradition still pulses through its alleys.

The shift to plastic containers, however, is a reflection of modern convenience. They're lighter, more durable, and easier to transport, especially by motorbike. Yet, this change has sparked concern among long-time curd makers and cultural purists alike, who fear the essence of Juju Dhau is being diluted.

What hasn't changed is the painstaking attention to quality that defines the preparation of the curd. Each morning, Rina and her team receive fresh milk from cows and buffaloes from nearby towns. It undergoes fat content checks -- the ideal being five per cent -- before moving to a commercial milk boiler that replaces the manual stirring of the past.

"After receiving the milk, the fat percentage should be checked, and the standard measurement is 5 per cent. After being approved, the milk is then boiled in a vat (pasteuriser) machine, before the milk needs to be stirred manually, which has now been replaced. After the milk hits up to 85 degrees Celsius, it is then transferred to a Dekchi (a big and deep utensil to boil things), where it is boiled for another hour. Thus, the boiled milk is transferred into the mud/plastic pitcher three times. The milk cannot be taken off the stove; rather, milk can be added onto it," Suwal explained.

The milk is poured in stages over an hour or more, forming layers of froth and cream. It's then cooled and inoculated with a starter culture -- a spoonful of existing Juju Dhau -- to begin fermentation. What follows is a slow and careful process of setting the curd, now aided by refrigeration.

Where once clay pots were insulated with blankets and rice husks to retain warmth and nurture the fermentation, refrigerators now quicken the process, allowing greater volumes to be made in a shorter time.

Despite this evolution, Juju Dhau's distinct taste remains a draw for locals and visitors alike. Himanshu Thakur, a tourist visiting Bhaktapur, shared his experience.

"First of all, the taste was slightly tangy but pleasantly sweet, and it is very different from normal curd because it's not very sour, not at all sour. It also has a much thicker texture than a normal Dahi (curd)," Thakur told ANI.

Buffalo milk -- with nearly double the fat of cow's milk -- is often credited with delivering this luxurious texture. Even today, traditional curd makers insist that real Juju Dhau must begin with buffalo milk to stay true to its origins.

The demand for the King Curd continues to surge, especially during festivals.

"During summer, we use 15 cans of milk, where each can contains forty litres of milk. During the festive seasons, we have to make Juju Dhau from 30 to 40 cans of milk," Suwal concluded.

As Bhaktapur changes with the times, so too does its beloved curd. But for makers like Rina Suwal, each batch remains a balancing act between heritage and modernity, between clay and plastic, ensuring that while the methods may evolve, the soul of Juju Dhau is never lost.