"Not a re-release. A resurrection": A film that once held us now holds time itself

Jun 28, 2025

By Suvir Saran

Mumbai (Maharashtra) [India], June 28 : I stood at the red carpet of Jio World Plaza the other night, draped in a silhouette curated by none other than Muzaffar Ali himself--together with his daughter, Sama Ali, under the label they've given the world, House of Kotwara.

It wasn't just fabric--it was a mood, a moment, a memory stitched into shape. And as I turned and faced the towering poster of Umrao Jaan at the entrance, I paused.

For a heartbeat, maybe longer, I forgot where I was. I didn't see Suvir. I saw Umrao. I saw Rekha, swaying in twilight silks. I saw Farooq Shaikh, smouldering in the dignity of doomed love. I saw Naseeruddin Shah, his presence both brooding and oddly angelic.

I saw the shadows, the silences, the veil between then and now. And somehow, absurdly yet unshakably, I felt as if I was not walking into a film screening--I was walking back into my own life.

That is the power of real art. That is what Muzaffar Ali does.

He doesn't direct. He conjures. He doesn't create costumes or characters--he builds atmospheres. He doesn't traffic in spectacle--he traffics in soul. His lens doesn't just frame a scene. It absorbs time.

And so, when Umrao Jaan returned to the big screen the day before yesterday at PVR INOX, this wasn't a re-release. It was a resurrection. A time warp. A collective heartbreak re-opened, re-experienced, and re-blessed.

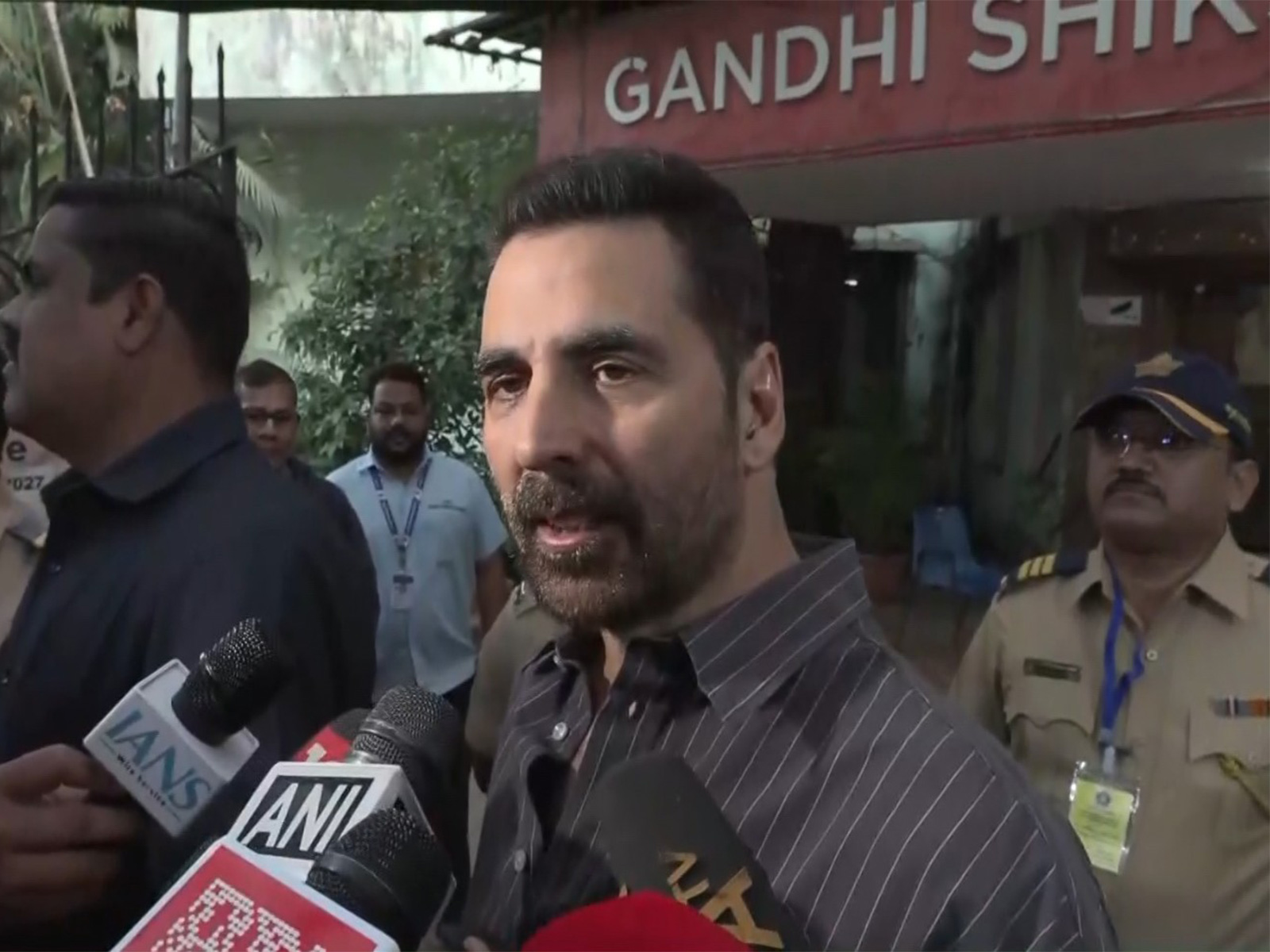

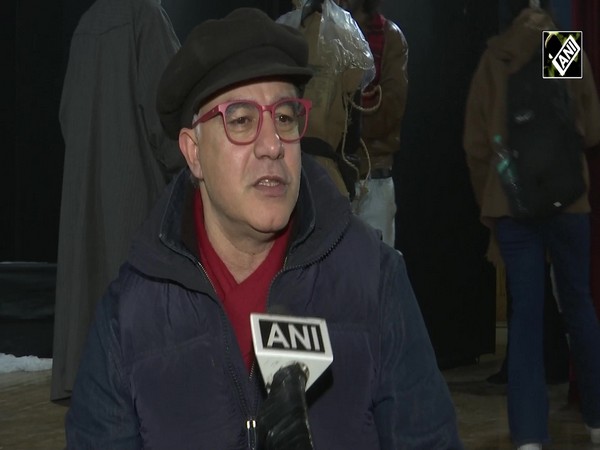

The celebrities came--Anil Kapoor, radiant and clapping; Alia Bhatt, glowing; Manish Malhotra in reverent hush; Jackie Shroff with a rogue tear; the daughters of Sridevi, luminous with legacy. Dream Girl Hema Malini, graceful as ever, took her place with quiet pride. Raj Babbar--himself a part of the original Umrao Jaan cast--stood among us, bearing both nostalgia and presence.

A.R. Rahman, gentle genius of music, was there too. Aamir Khan arrived with his sisters, despite the whirlwind surrounding the release of his latest film. Tabu, eternal and enigmatic, held court with eyes that still seem to read poetry mid-air. Vedang Raina and Vijay Varma were there, as were many others from the acting fraternity. Jitendra Kapoor, the actor of yesteryear and a man of enduring style, brought his sparkling charm.

Tanuja, radiant with history, added her unmistakable aura. And Adnan Sami, musician and master of modulation, arrived with quiet reverence. Each one came not merely as a guest, but as a devotee--to bow to a film, yes--but more so, to a feeling. We were not just celebrating cinema. We were saluting survival. Saluting a film that gave many of us, quietly and profoundly, the permission to live.

Because that's what Umrao Jaan did for me, I was barely nine, maybe younger, when it found me. Or maybe when I found myself in it.

In a world that had no name for me, no mirror, no map--I found sanctuary in a courtesan. In a tawaif. In a woman who danced through disgrace and rewrote it as dignity. In Rekha's eyes, I saw my fears dressed in kohl. In Asha Bhosle's voice, I heard my aching silence. And in Muzaffar Ali's vision, I found the first adult who understood me, without ever having met me.

"Yeh kya jagah hai doston?" wasn't just a lyric. It was a prayer. It asked what I had no words for. What is this place, this life, this world where I am neither fully welcome nor fully gone?

It whispered, "Even you, child, belong."

That whisper grew into a roar over the years. As I grew into myself, my queerness, my contradictions, I kept returning to that film like one might return to a shrine. It gave me language when I had none. It gave me elegance when I had only wounds. It gave me poetry when all I had was pain.

And how did it do that? Through the simplest alchemy--truth.

Muzaffar Ali dared to film the truth not loudly, but gently. Not with noise, but nuance. He painted not just what we see, but what we feel just before the tear falls. What we remember long after the song ends.

He did not make Umrao a victim. He made her a universe. He did not condescend to her. He crowned her. He filmed her like one films the moon--quietly, carefully, reverently. He gave her wajood--essence, agency, artistry. Through her, he told every "othered" person in the audience: you, too, are worthy of grace.

And then came Rekha. That role was not performed. It was inhabited. It possessed her. Or perhaps, she possessed it.

Every blink was a sentence. Every pause, a monologue. Every turn of her wrist carried centuries of unshed tears. She did not act sorrow--she distilled it. She didn't seduce with sensuality--she summoned with stillness.

Rekha ji, who stood in that theatre with us two nights ago, looking no less luminous than the woman she embodied on screen four decades ago, remains the eternal mirror of grief and grace.

And then there's Asha ji. What do I say about a 91-year-old nightingale who sang that evening not only with voice, but with memory? With mischief? With might?

She told us, without any fanfare, that when she heard Rekha had been offered the role of Umrao, she said to her, "Do it. You'll become a household name." She wasn't wrong.

And then she sang. Not a performance. A prophecy.

Every breath she took in Umrao Jaan was imbued with prayer. Every pause was poetic. Every alap carried longing. She didn't deliver songs. She delivered sanctity. She turned music into masjid. She made pain melodic, and melody immortal.

And between her voice and Khayyam's composition, they created a score that didn't just accompany a story--it cradled it. It swayed like a mother's lap. It stung like unspoken love. It floated like incense. It refused to hurry. It refused to please. It asked you to sit, to ache, to stay.

The words? Shahryar. That genius of ghazal. That weaver of verses that feel like wounds stitched in silk. Lines like "Kab mili thi, kahaan bichhdi thi..." or "Justuju jiski thi..." aren't just lyrics--they are lifelines.

So many of us have lived inside those lines. Have whispered them in loneliness. Have used them as shields, as salves, as spells to keep despair at bay.

And now, here we are--decades later. Older. Perhaps a little braver. Perhaps not.

We sat there the other night, a full house at PVR INOX, mouthing the dialogues before they played, clapping with each song, catcalling with abandon. We weren't watching a film--we were living it again. Because for many of us, it was never just a movie. It was our map. Our monument. Our memory.

We were people whose stories had never made it to the screen. Who had grown up with no reflection. And then, suddenly, Umrao Jaan shimmered into our lives and said, You too exist.

That is what cinema can do when it is made with soul. That is what Muzaffar Ali gave us--not content, not entertainment--but being.

The film didn't care about the box office. It cared about breath. About shadows. About how silk sounds when it sighs. About how poetry lands when it's not recited but lived. About how longing can sometimes be louder than love.

And here's the truth. I am still nine years old when I watch Umrao Jaan. I am still a boy sitting cross-legged in front of a TV, heart racing, unsure of his place in the world. But I am also forty-nine. I am also a man in a red carpet kurta stitched by hands trained by Meera Ali and Muzaffar Ali, hands that have stitched dignity into design.

I am both. I am all. And Umrao Jaan allows me to be.

That night, as we walked out of the theatre, people held hands tighter. Some looked misty-eyed. Some looked changed. I overheard someone say, "I didn't know films could feel like this." And I smiled.

Because Umrao Jaan isn't a film, it's a fragrance. It's a fog. It's the feeling of being seen when you never thought you could be.

And then--sometime after three, before the sky began its daily stretch--we arrived at the home of Shad Ali. Muzaffar Ali's son. Mumbaiite. Maverick. Impeccably dressed in a sherwani of quiet command. His home in Juhu felt far from Mumbai, and yet deeply of it--like a Lucknowi sonnet buried in a Mumbai night. We were fed a feast that wasn't just Awadhi cuisine--it was inheritance.

Dishes crafted by a cook who had served the family for 37 years, recipes learned from the grandmothers--Shad's maternal and Muzaffar's own. And with every bite, we drifted again--into Awadh, into lore, into memory. We weren't just guests. We were part of a continuum. That too is Muzaffar Ali's doing.

He doesn't let time fade--he lets it ferment, deepen, scent the present with the dignity of the past. He gives us food as feeling, homes as history, moments as museums.

Let yourself feel again.

Because some films pass time, others become it.

And this one--this shimmering, sorrow-soaked, saffron-scented epic--has already entered eternity.

Umrao Jaan lives. And because of her, so do we. (ANI/ Suvir Saran)

Disclaimer: Suvir Saran is a Masterchef, Author, Hospitality Consultant And Educator. The views expressed in this article are his own.